BERKELEY — Boeing’s defense business reported a quarterly profit Wednesday, even as losses deepened in the company’s troubled commercial airplane segment.

Companywide, revenues fell to $16.6 billion, from $17.9 billion in the same quarter last year. But Boeing also trimmed expenses, logging a $355 million loss, compared to the $425 million loss in the same quarter last year.

CFO Brian West told analysts Wednesday that the defense unit’s results took a $222 million hit from losses in two fixed-price development programs — $128 million in the KC-46 tanker program, and $94 million on the T-7A trainer plane, which is produced in the St. Louis area.

Fixed-price contracts have been an ongoing headache for the defense business. West noted that the U.S. Navy awarded Boeing a cost-typed contract modification for two MQ-25 refueling drones, also produced locally.

People are also reading…

Last month, the company secured a $1.3 billion contract from the U.S. Navy for 17 fighter jets manufactured in St. Louis County. The contract extends the F/A-18 “Super Hornet” production line — expected to sunset in late 2025 — into the spring of 2027.

West and CEO David Calhoun spent much of an hourlong conference call Wednesday fielding questions from stock analysts about the pace of production at factories that manufacture passenger jets, which have been under intense public scrutiny since a panel blew off a brand-new Alaska Airlines 737 Max in January. Investigators say bolts that help keep the panel in place were missing after repair work at the Boeing factory.

Boeing’s defense business, which largely operates out of the St. Louis area, is in a separate unit from the aerospace company’s embattled commercial plane segment. But the one isn’t entirely separated from the other. Experts say the company in the past has based bets in its defense business — like the trainer and the drone — on the assumption that it could expect healthy revenues from the 737 passenger jet.

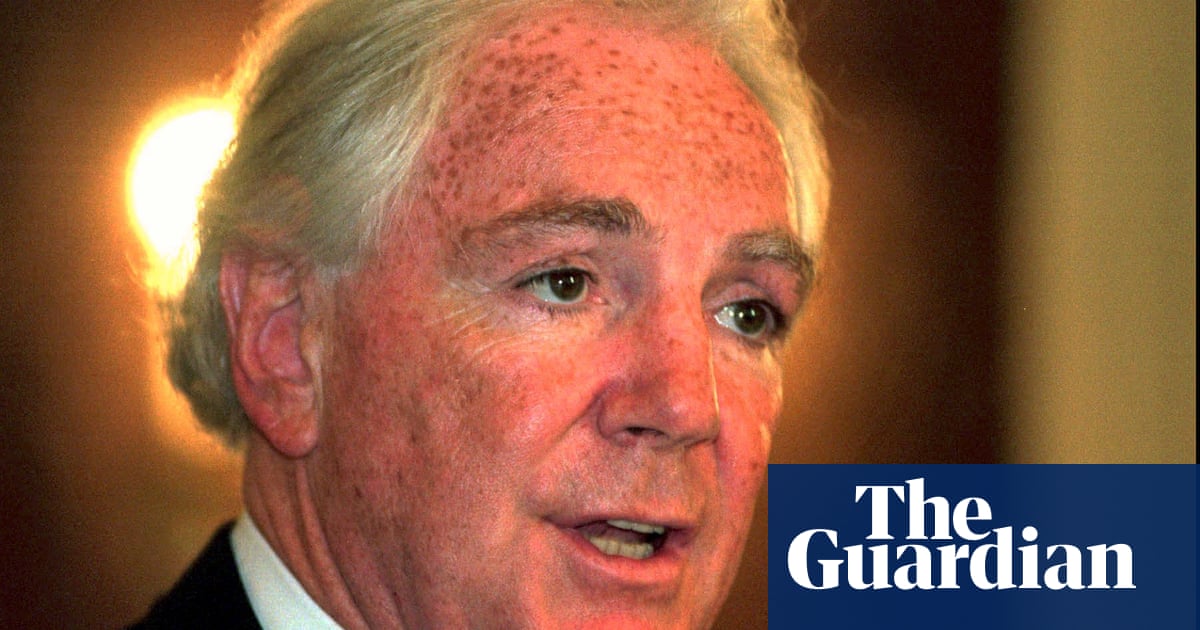

Calhoun, who plans to step down at the end of the year, hinted Wednesday that he has an internal candidate in mind as a successor. The board will make the decision. Calhoun said he doesn’t expect an announcement in the next month or two.

Calhoun served on the board before his appointment to the chief executive role in January 2020. He replaced Dennis Muilenburg, who was fired in the 2019 aftermath of the 737 Max crashes.

Calhoun said he has told the board that the job needs to go to a long-term thinker.

“You know as well as anybody, maybe better than anybody, how long-term this business is,” Calhoun told an analyst. “Mistakes that matter are usually in the development of another airplane.”

Issues with production, like the ones Boeing is currently struggling with, or the supply chain woes of the COVID-19 pandemic are relatively short-term problems, in the context of aviation, he continued.

“On the other hand, when you get big development programs wrong, you pay a price, and you pay it for a long time. And I know an awful lot about that,” he said. “So my view is, that next leader has to be prepared to make smart, long-term decisions and get the development programs right. That’s the prescription that I’ve offered the board.”

View life in St. Louis through the Post-Dispatch photographers’ lenses. Edited by Jenna Jones.